Maguro Sushi

True Tunas

What is Maguro (True Tunas)?

Maguro is a general Japanese name for the genus of the “true tunas“, which belong to the mackerel, tuna, and bonito family. In Japan and many other parts of the world, they are considered a sought-after fish and are traded at considerable prices depending on the species.

Even though the generic term maguro covers several species, bluefin tuna species are preferred to the other species, especially in high-end restaurants. Bluefin tuna is called hon maguro (本鮪) in Japanese, which literally means “genuine” or “true tuna”. Given the iconic importance of bluefin tuna within the maguro group today, the following article is mainly dedicated to it.

Maguro as Ingredient for Sushi or Sashimi

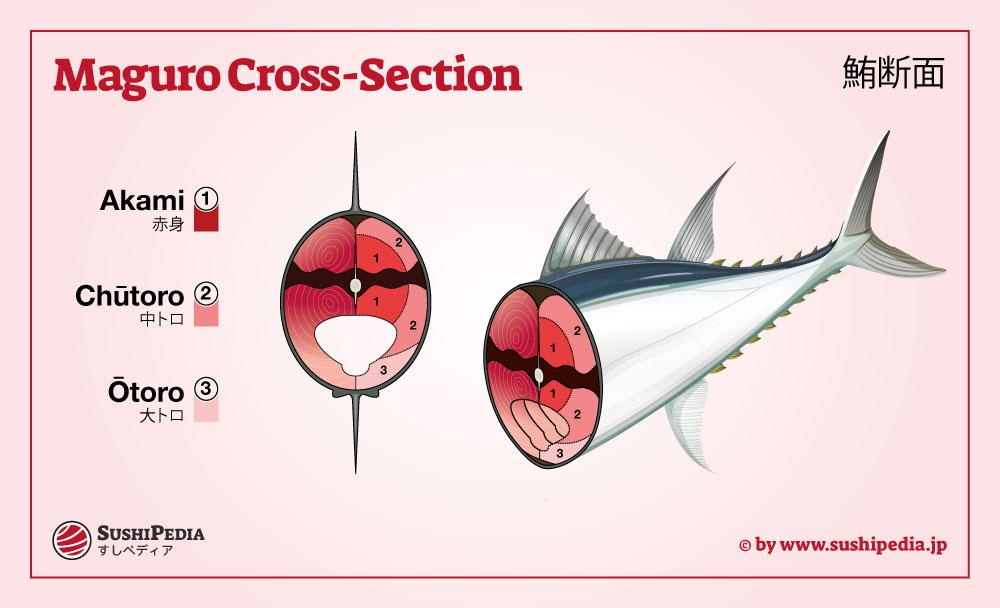

The taste of maguro sushi or sashimi depends on the species of tuna and the part of the body from which the meat is taken. In general, the tuna meat is very tender and has an intense taste. Meat that comes from the center of the body is dark red, shiny and very lean, it is called akami (赤身) in Japanese. Akami has a fine sour taste which is accompanied by full-bodied umami aromas. The texture is velvet-like and firm without being tough.

“And shibi (adult bluefin tuna), good to make nigiri with and good to roll, is surely worthy to be called “the King of Sushi“.

- Jiro Ono, Sushi Chef (Sukiyabashi Jiro) [Satomi, 2016]

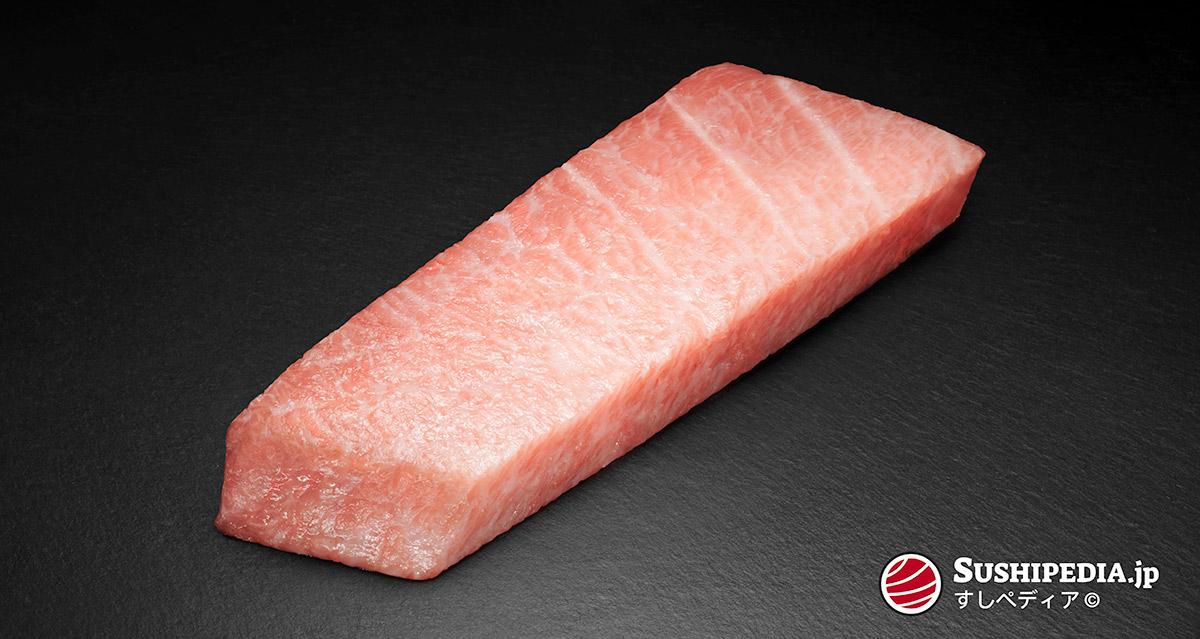

The fatty meat of maguro is known as toro (トロ), derived from torori (とろり) and symbolically describes the feeling of toro, which literally melts on the tongue. Toro is mainly located on the back and belly of the maguro body. It is exceptionally tender, very rich in fat, and has an intense, sweet buttery taste that is unmistakable.

Aging Tuna for Sushi

Sushi chefs (itamae, いたまえ) skilled in their craft age the blocks of maguro meat up to several days, traditionally in ice or nowadays usually under refrigeration. During the aging process, the meat loses its odor and in return gains taste and tenderness. The duration of the process depends on the quality and condition of the maguro and must be well balanced. If the meat matures for too long, it loses too much of its characteristic colour and appears less appealing. In addition, the sinewy separating layers (suji, 筋) lose too much firmness and can no longer hold the fatty meat in shape, especially pieces from the belly area.

A study by the University of Tokyo in cooperation with the Japanese restaurant chain Kura Sushi confirmed that the taste of maguro intensifies when the meat is matured under controlled climatic conditions. In upscale sushi restaurants, the aging process is individually adjusted according to the preferences of the sushi chef and the quality of the maguro meat, which can take up to several days to weeks. Mastering the ageing process - and in particular the microbiological quality - of meat depends on controlling good hygiene practices and environmental conditions.

Best Season

The fat content of maguro depends on the season and its catch region. Specimens caught in cold sea regions, before the spawning season, have the highest fat content and are therefore most sought-after.

The best season for maguro, which comes from the North Pacific, is between September and January. During this time of the year it stores more fat in his belly and back regions. Maguro from tropical waters spawns all year round and is therefore available through the year in varying quality. The best season for maguro from the Atlantic Ocean, caught in the Gulf of Mexico, is between January and April. For the East Atlantic stock of maguro the best season is October to April.

Maguro fattened in aquaculture facilities is available all year round in consistent quality.

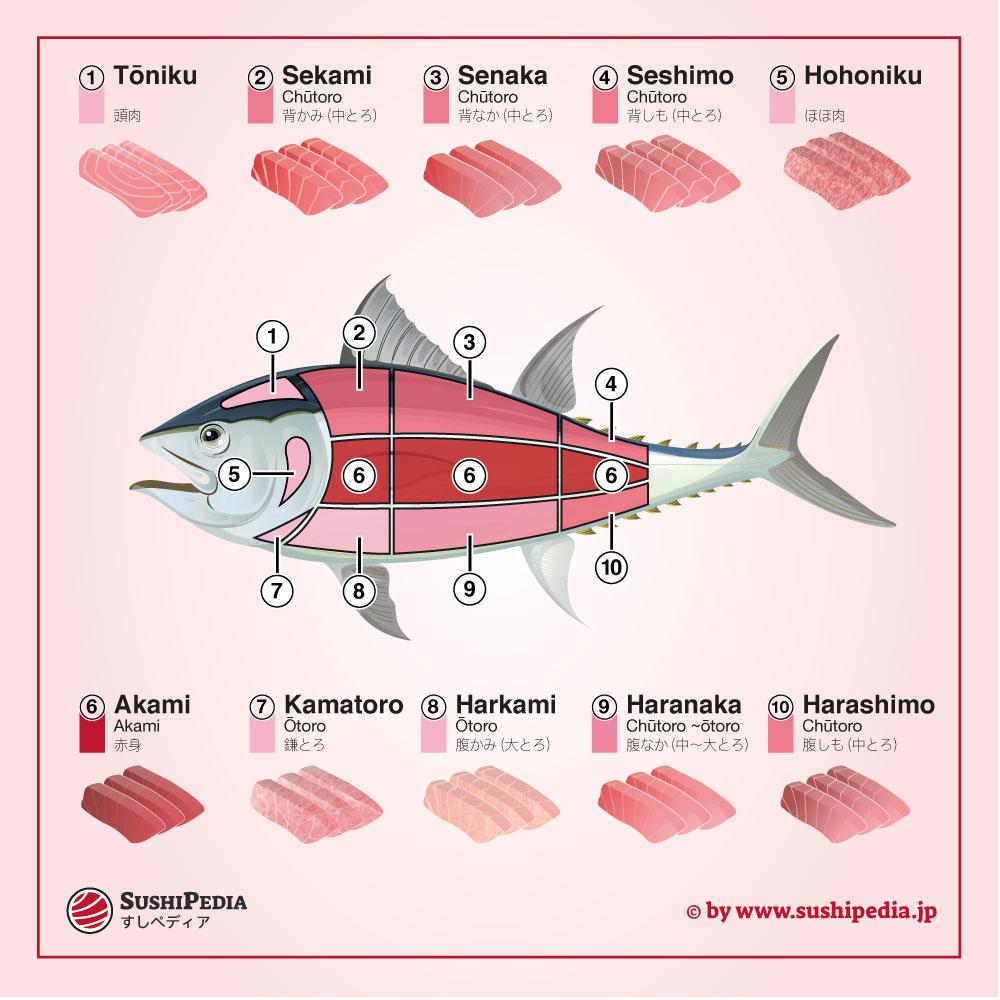

Meat Types of Maguro for Sushi & Sashimi

The meat of maguro can be divided into three sections:

- The frontmost section is called kami (かみ

- The middle part is referred to as naka (なか)

- The rear region is named shimo (しも)

These three sections are subdivided into back (se, せ) and stomach-part (hara, はら). Furthermore, the forehead (touniku, とうにく or noten, 脳天のうてん) and gill or collar meat (kama toro, かまトロ) can be used and are considered a special delicacy.

In the meat from the dorsal section, the strips (sinew or tendon plates) are thicker in the front region (kami) and thinner within the rear section (shimo). The middle section (naka) is the least streaked and accordingly higher in price. Meat from the region of the belly is fattier the closer it is to the gills. With increasing direction to the rear back section (shimo), the fat content decreases and therefore also the price.

Akami あかみ [赤身]

Meat from the center of the maguro is very low in fat and has a striking red color. Lean red meat is called akami in Japanese. The average proportion of akami is about 60% of maguro and is therefore cheaper than toro (トロ) The lean akami meat is rich in minerals, L-α amino acids and hemoglobin, which contain iron ions, giving the meat its subtle metallic taste, which are accompanied by a refreshing acidic flavors (sanmi, 酸味).

“The essence of maguro lives in the lean meat. Sushi lovers, eat your lean meat.

- Jiro Ono paraphrasing food critics, Sushi Chef (Sukiyabashi Jiro) [Satomi, 2016]

Akami from the middle region (senaka, 背ナカ) is particularly tender and pleasant savory in taste (umami). It is considered the highest quality akami meat by most chefs [Nakahara, 2019]. The term akami is not always found on menus, usually the term “maguro sushi” or “maguro sashimi” refers to the reddish lean akami meat.

Maguro Zuke マグロ漬け

Before the advent of modern refrigeration technology, tuna could only be transported over short distances. Without any kind of preservation, the tuna would have spoiled before reaching the cities. Therefore, tuna needed to be preserved by soaking the meat in soy sauce. The reddish lean parts of tuna (akami) were used for this, because unlike the fatty parts, these absorb the sauce better (less hydrophobic).

The salt contained in the soy sauce and the exclusion of air have a positive effect on the shelf life of the meat. In addition, the sauce functions as a seasoning, because it is rich in amino acids and contains umami components. By soaking, the umami component is added to the meat or already contained umami components are strengthened. In addition, the texture changes, the meat becomes firmer and the surface at the same time more velvety. In addition to pure soy sauce, individual mixtures are used as desired, which still contain mirin and sake, for example. The pickling time depends on the personal taste, so that the range can extend from subtly mild to intensely salty.

Tokujō No Akami 特上の赤身

The highest quality akami meat comes from the middle part of the tuna (naka). The area near the center of the body, where the vertebrae are located, is called the tenmi (天身), which is darker in color and triangular in shape. It is considered most premium akami meat (tokujō no akami), which tastes intensely of tuna and has very few sinew layers. The consistent dark color and velvety texture make it a very popular ingredient for hand-shaped sushi (nigiri) or sashimi.

Chutoro ちゅうとろ【中トロ】

Chuturo is taken from parts of the back and abdomen of the maguro, it accounts for about 30% of the total quantity and is therefore priced between akami and otoro. The meat is extremely tender and has a slightly sweet buttery taste.

Chutoro: Enpitsu えんぴつ

If a hon maguro is particularly large and rich in fat, it is possible to separate a fine strip between the chutoro meat and the skin. This elongated narrow section is nicknamed “pencil” (enpitsu, えんぴつ). Enpitsu is marbled, extremely tender and has a full-bodied taste. Sushi master Jiro Ono lovingly describes it as the “King of Chutoro”. Since tuna fish of special quality is needed for enpitsu, this cut is rarely available even in very high-quality sushi restaurants and is usually reserved for their regular customers [Satomi, 2016].

Chutoro: Hime ひめ

The middle region (senaka) is considered to be of particularly high quality meat. Within this section, below the dorsal fin, is the hime (ヒレ) fillet. This relatively small section is of special chutoro quality. This special and relatively small piece of meat impresses with its particularly smooth texture, is free of sinew and less oily.

Chutoro: Hagashi はがし

From the seneka area can be taken hagashi, which is also called “streakless chutoro“ (筋なしの中トロ). The flesh comes from an area near the dorsal fin, approximately where the veins run. Along with hime and enpitsu, these are considered the best parts of medium-fat tuna meat. The meat called hagashi or wakaremi (ワカレミ) is either cut into strips or carefully peeled off in strips one at a time. The texture is extremely fine and soft. It is a particularly prized ingredient for nigiri sushi that is usually only found in sophisticated sushi restaurants.

Otoro おおとろ【大トロ】

The particularly fatty abdominal fat that envelops the organs of the maguro is called otoro. In Japanese the character 大 means “physically large”, in the context of toro ("literally melts on the tongue") it stands for "extreme" or "extra" and can be read as a long “o“ (おお). So otoro is the part of the tuna that feels extremely soft on the tongue and melts away, thanks to its extreme fat content. The taste of the fatty otoro meat is very different from the lean red akami section.

It was not until the advent of modern refrigeration technology, a growing infrastructure and a prospering economy that maguro sushi took on the diverse characteristics we know today. Suddenly it became possible to introduce the fatty otoro parts that had previously spoiled too quickly [Nakahara, 2019]. Due to its high fat content, toro has a water-repellent effect (hydrophobic) and could not be preserved with soy sauce at that time, as akami could (tsuke, ヅケ). Until the postwar period, toro was considered a low-quality fish (gezakana, 下魚) or pejoratively called neko matagi (猫またぎ), something even a cat would spurn [Ikuta, 2010], [Chiezo, 1992], [Tokyojin, 2007].

Shimofuri Otoro しもふりおおとろ【霜降大トロ】

The foremost area of the hara kami region is particularly noteworthy. At the top, just below the gill cover, there is fine marbled otoro meat (shimofuri, しもふり), whose structure is reminiscent of snow and the fine grain resembles the meat of the highest quality wagyu-cattle.

Jabara Otoro じゃばらおおとろ【蛇腹大トロ】

Besides the marbled shimofuri otoro, the jabara (蛇腹), haramo (ハラモ), or sunazuri (すなずり) called meat is found in the underbelly of the maguro. Of all the regions, jabara otoro contains the most fat, but also the most sinews. Because of the high percentage of sinews, the meat must be aged sufficiently, otherwise the meat would be unpleasantly tough. When processed properly, sushi or sashimi from jabara otoro rewards with an exceptionally sweet taste, smooth texture and extremely soft consistency that almost dissolves on the tongue.

The meat from this region can also be processed like chutoro wakaremi to hagashi, in which it is finely peeled off or cut from the sinews layers. This skillful separation results in a distinctly delicious piece of otoro that delights in both flavor and texture.

Negitoro ねぎとろ【ネギトロ】

Authentic negitoro consists of meat that is trimmed from the bone of the maguro (nakaochi, 中落ち) or of scraped meat and fat from muscle parts or the skin (sukimi, すき身). The negitoro meat is mainly used for gunkan-maki sushi or as a topping for rice.

In inexpensive restaurants, like most conveyor belt sushi restaurants (kaiten zushi, 回転寿司), mostly ordinary lean meat, chopped up and mixed with cooking oil or other additives, is used as a substitute for negitoro. Authentic negitoro is very tender, has a creamy texture that melts on the tongue and tastes slightly sweet. The crispness of a nori leaf pairs very well with its extraordinary soft consistency.

Kama toro かまとろ【鎌トロ】

Kama toro or kama shita (かました) is one of the most marbled (fatty) pieces of tuna meat. It is located in the lower part of the collar band of the maguro. It is a triangular shaped region that is located under the gill cover and in front of the tuna's belly. Therefore, only two small pieces can be taken from a maguro at a time. Even with very large individuals, the proportion of total meat is well below 1%. The meat is heavily interspersed with oily connective tissue and tendon plates, but is still very tender due to its extreme fat content. It is by far the greasiest meat in tuna and accordingly highly priced and sought-after.

It should be noted, however, that the meat is extraordinarily fatty. Occasionally, sushi chefs receive feedback that kama toro is too greasy for some customers.

Toniko とうにく【頭肉】

Toniko or noten (のうてん, 脳天), is the meat from the head, respectively the forehead, of the tuna. It accounts for less than 1% of the total tuna. Some fishmongers like to keep it for themselves instead of selling it. The pattern of the connective tissue is characteristic for toniku, instead of parallel it is concentric.

Hohoniku ほほ肉

Meat that comes from the cheeks of tuna is called hohoniku in Japanese. Hohoniku is generally used cooked as a side dish to other dishes. For preparation as nigiri sushi, it is usually heated as well, either completely or with the raw core remaining (tataki, 叩き). The texture is elastic with a balanced balanace of fat and red meat.

Maguro in Japan

Japan and Bluefin Tuna

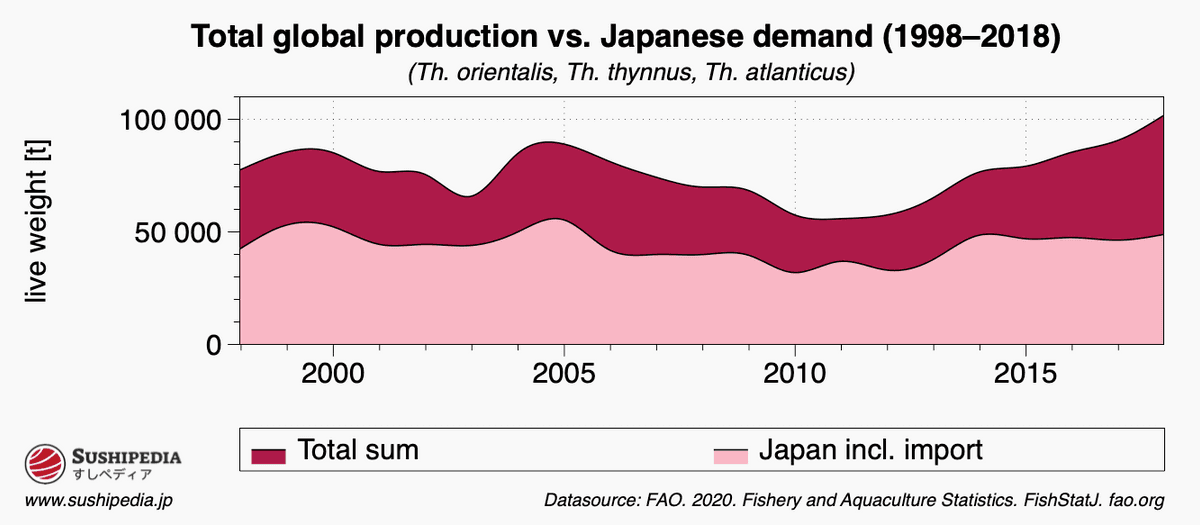

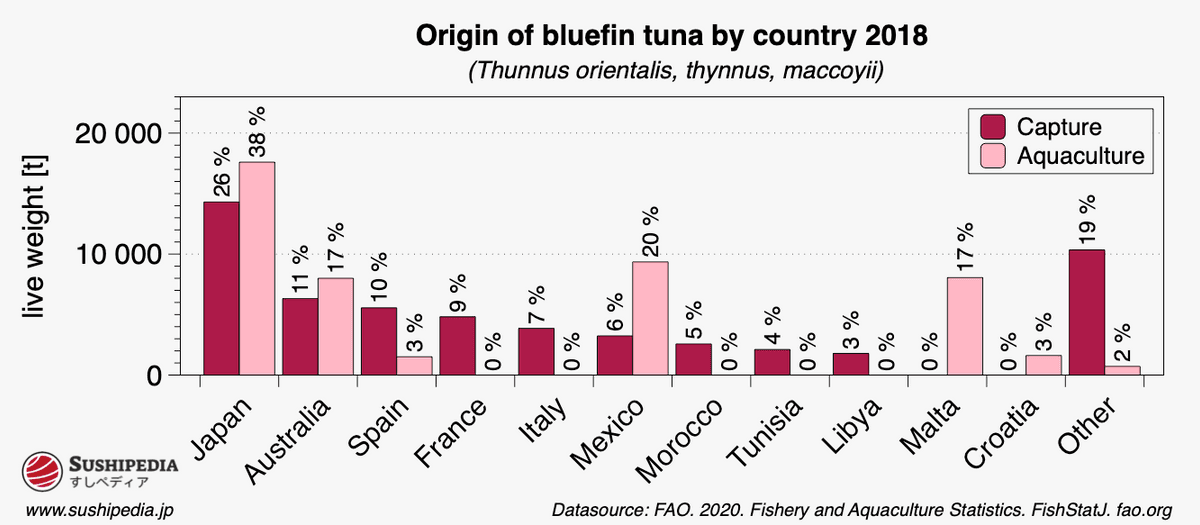

Japan is the world's largest consumer and importer of bluefin tuna (hon maguro), the majority of the world's catch is shipped to Japan to be served as sashimi and sushi. Main exporters of bluefin tuna to Japan are Australia and South Korea. Japan is not only one of the biggest importers but also one of the biggest fishing nations. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in 2018 Japan's share of the global catch of bluefin tuna was over 25%, putting it ahead of Australia (17%). Taking into account Japanese imports and catches, Japan claims well over half of the world supply of bluefin tuna (hon maguro). It can be seen that the Japanese demand for bluefin tuna is relatively constant.

In old and pre-industrial Japan, the only way to preserve the freshness of fish and seafood was to keep them alive in basins filled with seawater, but the body size of tuna made this impossible. Only by the emergence of soy sauce maguro could experience a spread beyond the Japanese fishing villages. At this time, people began to preserve food by preserving it in a customized soy-alcohol sauce (zuke, ヅケ), including the lean meat of maguro. With the invention and spread of industrial freezing, the fatty toro meat also found its way to Japanese consumers. Until then, toro was considered inferior and not very tasty. Only by the rise of other fatty foods did the dietary and taste habits of the Japanese change so much that the triumphal advance of toro took its course to its current, almost iconic position in sushi gastronomy.

“The younger generation has grown up with hamburgers and meat [...] They want fatty fish like salmon or fattened farmed bluefin tuna.

- Yamamoto Takaichi, Misaki Tuna Auction Director [Adolf, 2019]

Whoever goes to Japan today to find first-class bluefin tuna (hon maguro) should go to Oma (ōma machi, 大間町) in the prefecture of Momori. The tunas caught in the Tsugaru Strait (tsugaru kspanikyō, 津軽海峡) off the coast Omas have an almost legendary reputation in Japan. Tuna from Oma is a protected geographical indication in Japan, which is associated with a lot of prestige. Oma gained national attention when a bluefin tuna (hon maguro) weighing 440 kg was landed there in 1994. Since then, Oma maguro has been selling at record prices at auctions, such as in 2001, when a tuna was auctioned at the Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo for the equivalent of over 170 000 U.S. dollar.

Important centers of tuna fishing are in the prefecture of Shizuoka and Miyagi In addition to Oma, tuna from Sado and Kii-Katsuura also play a central role, especially in top gastronomy.

The most expensive fish in the world

Until the 1960s, bluefin tuna was a rather cheap fish. Initially fueled by the early upswing of the Japanese economy, the global triumph of sushi led to an explosion in demand, which drove the price of bluefin tuna to heights unimaginable at the time. Thus, prices rose by more than 270% within the period of 1970–1980 years.

The price of maguro, especially hon maguro (bluefin tuna), depends not only on the quality but also on the season, fishing region and whether the fish is farmed. Of all tunas, hon maguro is the most expensive, because the number and quality of the caught fish is more influenced by climatic conditions than the quantity of fish ranched in fish farms. The meat of a farmed maguro can be more than half the price of a comparable specimen in the wild.

Every New Year's Day, the first auction of the year is held at the Tokyo Fish Market. The auction, which has become famous all over the world, is of no importance for the top gastronomy. It serves much more as an advertising and PR platform for large operators of sushi restaurant chains. The high prices that are achieved there every year do neither reflect the market price nor the quality of the auctioned fish. Among restaurant operators it is associated with great prestige and status to participate and win. It is well known that a winning bid gets a global media coverage, especially when a new record price is called.

Characteristics & Ecology of Maguro (True Tunas)

Classification by age

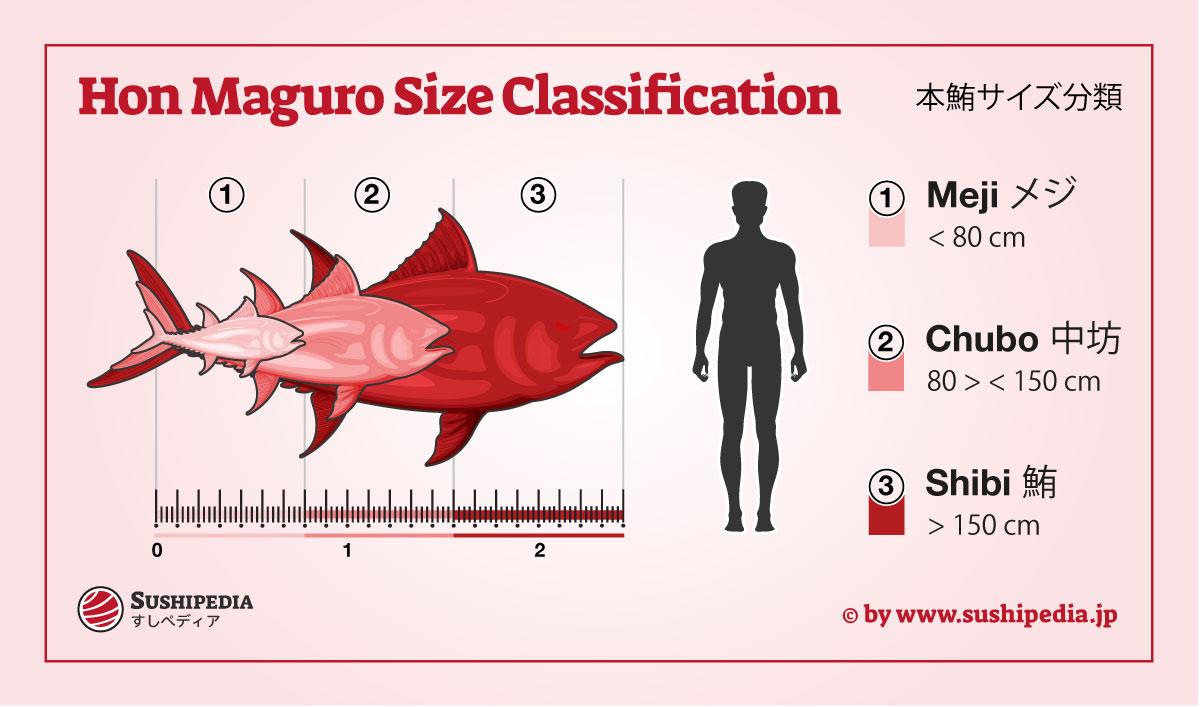

Bluefin tuna (hon maguro) has different names in Japanese depending on age and size:

Meji めじ【メジ】

The term mejimaguro refers to very young hon maguro whose weight has not yet reached 10 kg. Scientific research shows that it takes up to 3 years for a bluefin tuna to reach the weight of 10 kg. The meat of a mejimaguro still lacks the distinctive red coloration and is more similar to that of bonito (katsuo, 鰹). In summer the young tunas are to lean, meaning that they are mostly used only in winter for the preparation of Sushi or Sashimi. In general mejimaguro are significantly cheaper than older specimens.

Chubo ちゅうぼう【中坊】

The character 中 is read in Japanese Go- and Kun-reading as chū (ちゅう) and stands for medium or average (neither good nor bad). The second character 坊 is understood after the Go reading as bō (ぼう) and means boy or monk. Accordingly, chūbō is understood as an average animal or metaphorically interpreted as a temple boy; someone who still grows into the status of a monk.

In this stage of life a chubo maguro is up to 50 kg, has an approximate length of one and a half meters and an age of 3 to 5 years. The taste and fat content of a chubo maguro is already more pronounced than that of a meji maguro, but still does not come close to the quality of an big adult tuna.

Shibi しび【鮪】

The Japanese character 鮪 is read in the Kun reading as maguro and shibi. Shibi is also the old Japanese term for tuna and nowadays represents adult specimens. Shibi maguro have reached sexual maturity, have an average length of about 2 meters and weigh about 170 kg. Tuna that are especially large and heavy are nicknamed jumbo maguro and can exceed a weight of 270 kg and reach an age over 20 years.

Economy

Overfishing

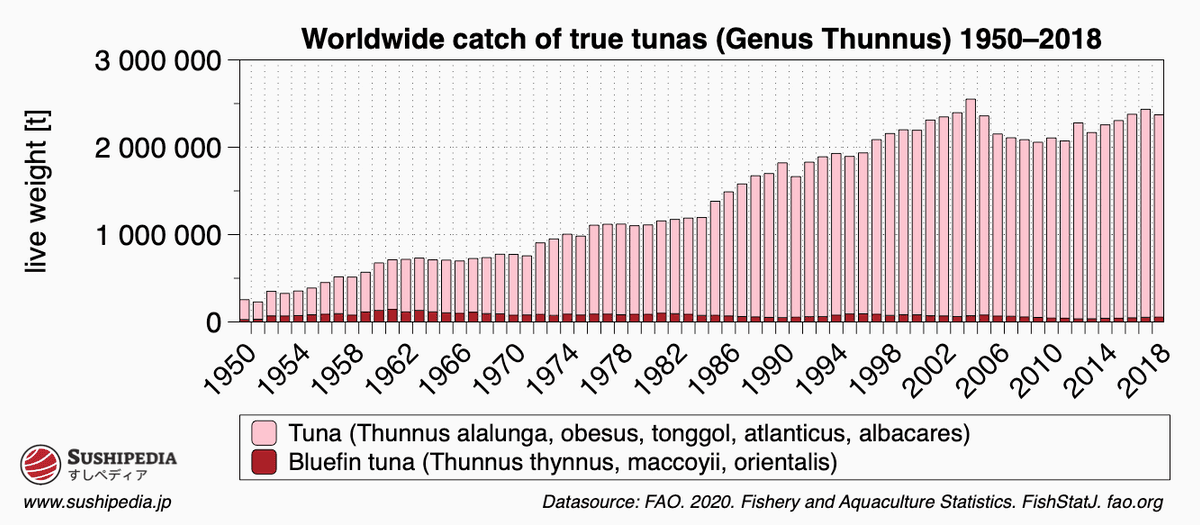

The growing demand, especially the global sushi trend and the resulting rise in prices have fuelled the overfishing of tuna around the world, making international resource conservation necessary.

Except for the long-tail tuna, for which no data is available, and the blackfin tuna, the only representative of its species considered not endangered, all natural populotions of tunas are threatened by overfishing. Especially the bluefin tuna, which is called hon maguro in Japanese, is heavily overfished. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the southern bluefin tuna is already threatened with extinction. Referring to the IUCN, all three species of bluefin tuna are clearly overfished. Attempts to protect them were thwarted in recent years by representatives of national fishing interests. During the CITES convention in Doha in March 2010, Monaco and the European Union presented the proposal to ban the trade in bluefin tuna. Japan, Canada and several member states of the Arab League vehemently rejected the proposal. A subsequent vote on the proposal led to a clear rejection of the proposal with 20 votes in favour, 68 against and 30 abstentions (CITES, 2010).

Aquaculture

Tunas are generally considered difficult to cultivate because of their ecological requirements. Especially the expensive bluefin tuna, which is highly valued in the top gastronomy, is particularly difficult to raise in aquaculture because of its sensitivity to spawning conditions. In Japan, research on the breeding of bluefin tuna was started in the 1970s, but it was not until 2002 that the first breakthrough relevant to commercial farming was announced. The focus of the research is the commercially feasible complete aquaculture, in which in the long run no more fish have to be taken from natural populations. For more than 30 years the Kindai University has been researching the breeding of bluefin tuna. In 2004 the first hon maguro bred from artificially fertilized eggs was shipped to the market. This is the first time the researchers have succeeded in creating a commercially viable breeding cycle. The Kindai University in Wakayama breeds and sells Pacific bluefin tuna (kuromaguro) under the brand name kindai maguro. The breeding takes place mainly on the coast of Kushimoto in Wakayama Prefecture.

The aquaculture tuna currently in the market is almost exclusively bred using the ranching method. In this method, specimens are taken from the wild, transported to netted enclosures and fattened there throughout the year. Since no relevant differentiation between young and old animals is made in the selection of wild animals, a significant proportion of animals miss the chance to reproduce. This process is therefore a significant threat factor to global tuna stocks.

Maguro in aquaculture are mainly fed with sardines and mackerels and reach their marketability after about two years at a weight of about 100 kg. In contrast to wild maguro these are smaller and have a less firm meat. On the other hand, controlled feeding makes it possible to ensure a consistently high body fat content, which leads to a higher yield of toro meat. Even though wild-caught tuna is still the non plus ultra among sushi gastronomes in terms of taste and quality, maguro from aquaculture also offers less affluent consumers a cheaper alternative.

Gallery

Further information on the author can be found in the section on image credits.

Video about Maguro

External video embedded from youTube.com: 江戸前寿司日ノ出茶屋 横浜. 高級本マグロ大トロ、中トロ、赤身すべて取れるハラナカのサク取り 〜How To Make Tuna Sushi〜

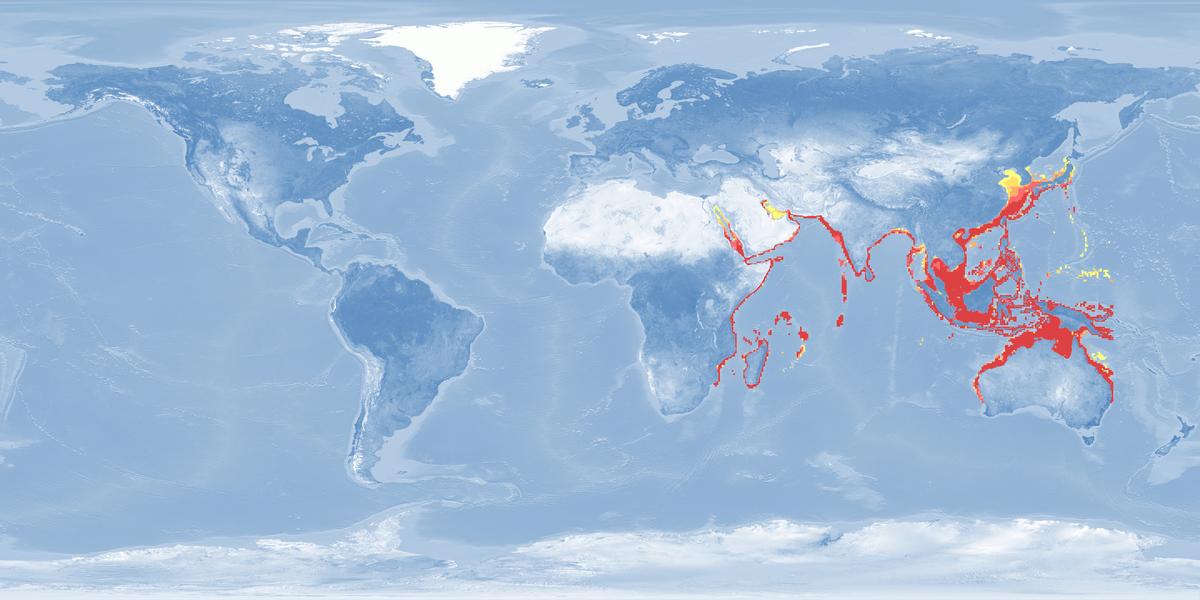

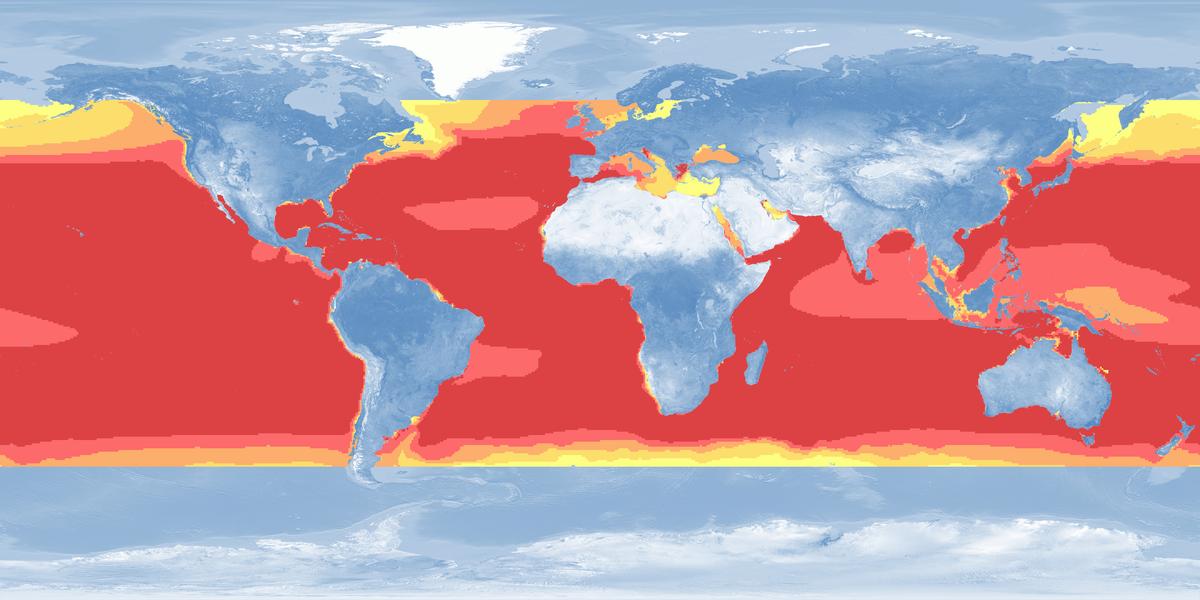

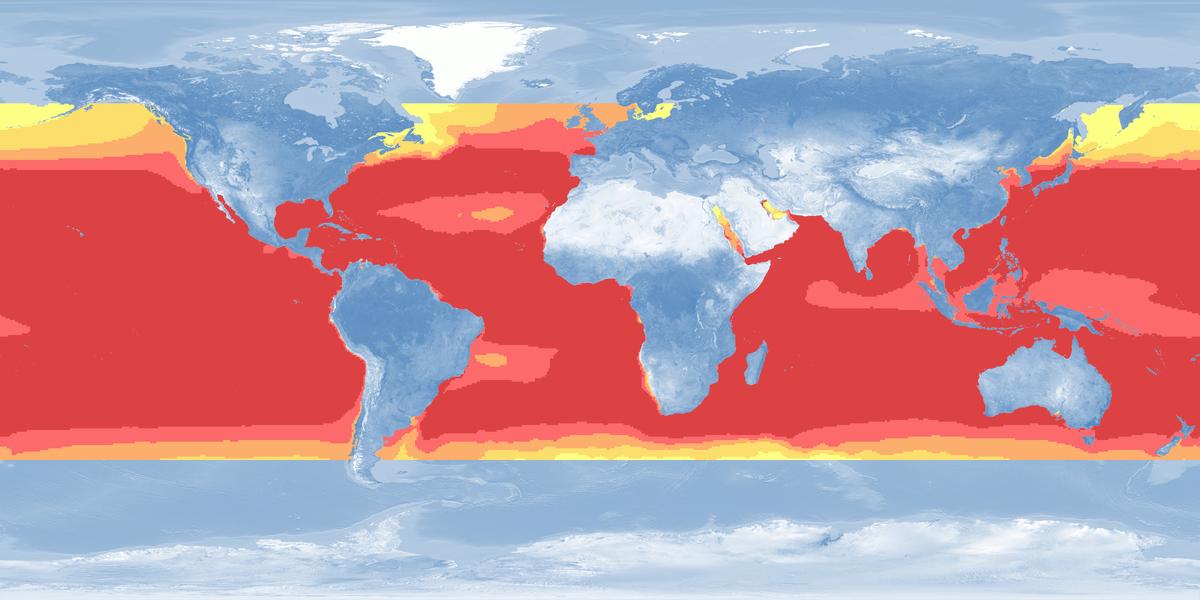

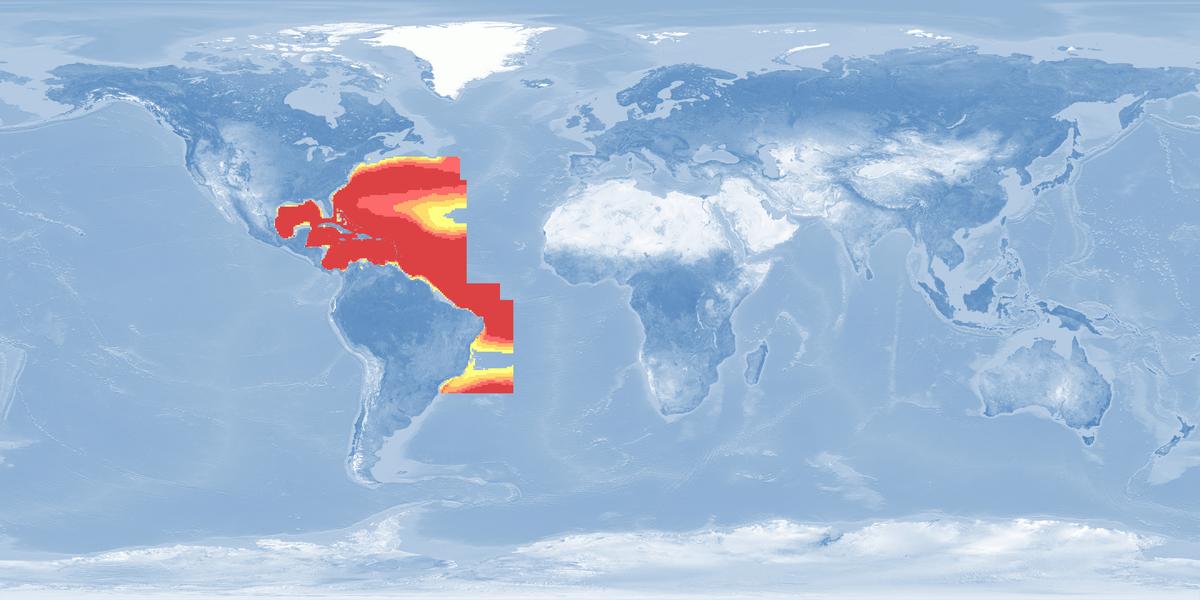

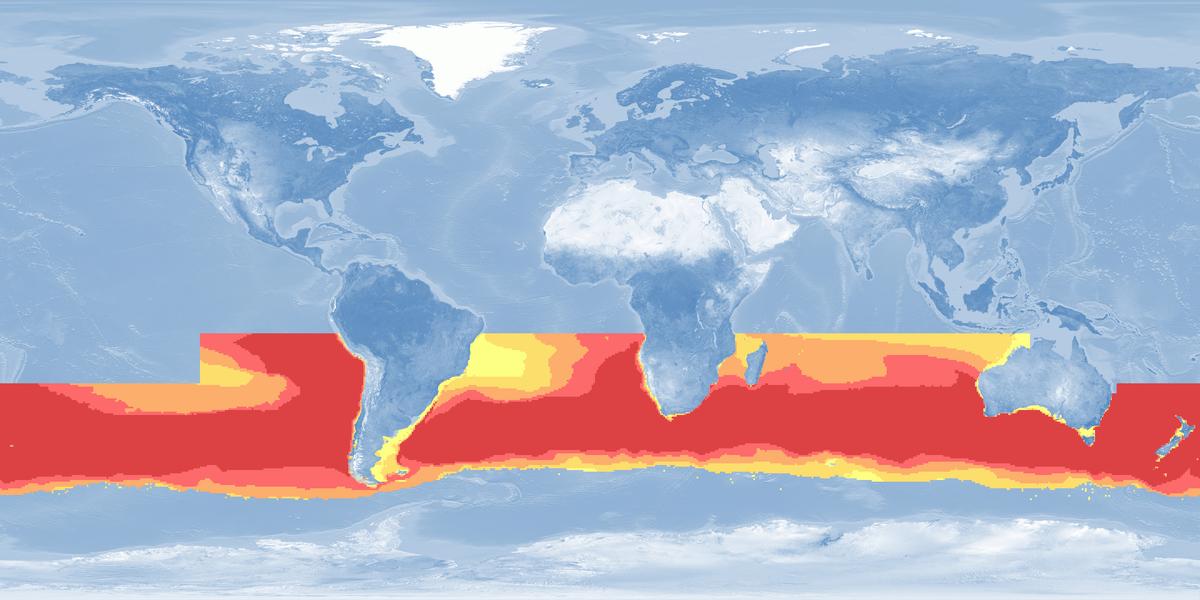

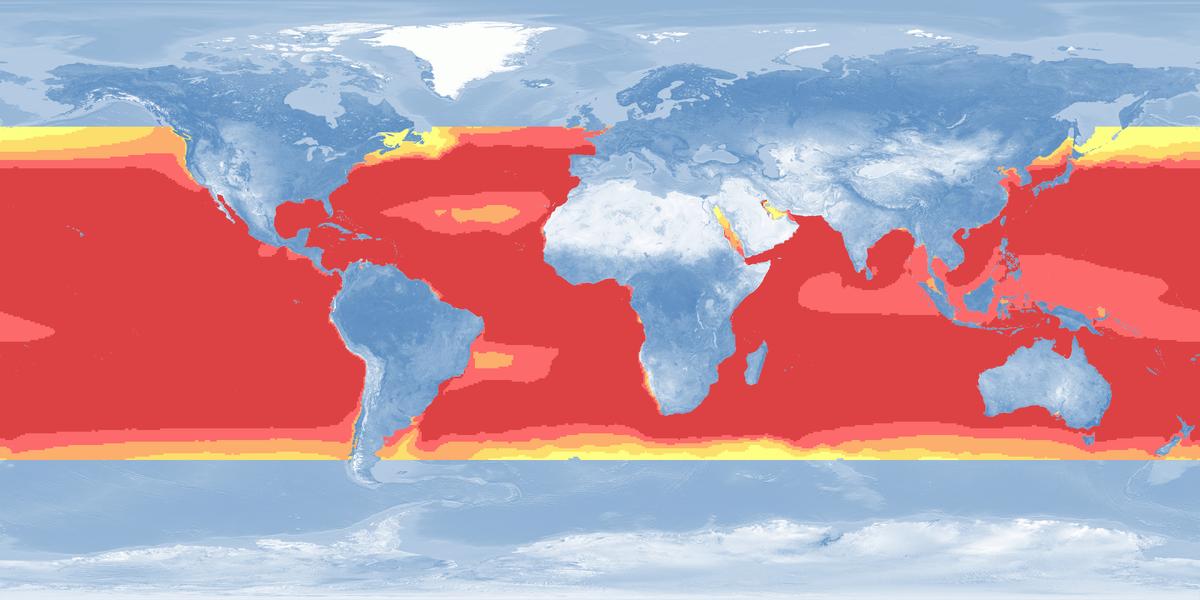

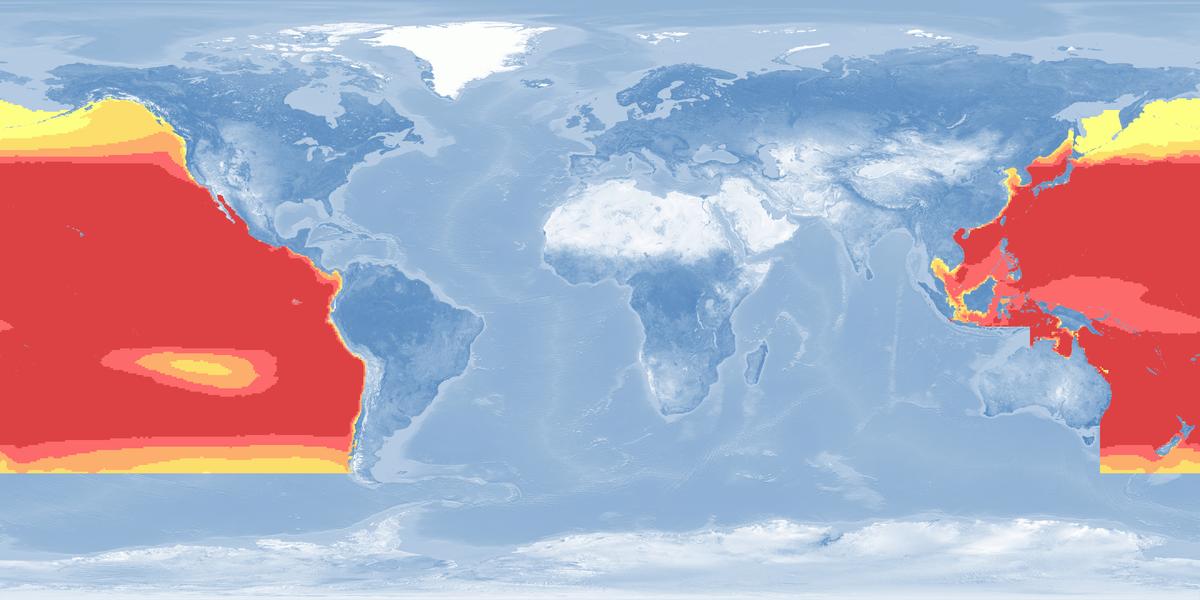

Distribution Area of Maguro

Source: Kaschner, K., Kesner-Reyes, K., Garilao, C., Segschneider, J., Rius-Barile, J. Rees, T., & Froese, R. (2019, October). AquaMaps: Predicted range maps for aquatic species. Retrieved from https://www.aquamaps.org. Scarponi, P., G. Coro, and P. Pagano. A collection of Aquamaps native layers in NetCDF format. Data in brief 17 (2018): 292-296.

Species of Maguro

The following species are regarded as authentic. Either historically, according to the area of distribution or according to the common practice in today's gastronomy:

Japanese Name | Common Names, Scientific Name |

|---|---|

binnaga, abako ビンナガ、アバコ 鬢長、蜻蛉鮪 | albacore, long-fin tunny, long-finned albacore Thunnus alalunga family: Scombridae |

kihada, kihadamaguro キハダ、キハダマグロ 黄肌、木肌 | yellowfin tuna Thunnus albacares family: Scombridae |

koshinaga, koshinagamaguro コシナガ、コシナガマグロ 腰長鮪、腰長 | longtail tuna, oriental bonito Thunnus tonggol family: Scombridae |

kuromaguro, hatsu クロマグロ、ハツ 黒鮪 | pacific bluefin tuna Thunnus orientalis family: Scombridae |

mebachi, bachi-maguro メバチ、バチマグロ 目鉢、目撥、鉢鮪、撥鮪、眼撥 | big-eye tuna, bigeye, bigeye tuna Thunnus obesus family: Scombridae |

minamimaguro, indo-maguro ミナミマグロ、インドマグロ 南鮪 | southern bluefin tuna Thunnus maccoyii family: Scombridae |

taiseiyoukuromaguro タイセイヨウクロマグロ 大西洋黒鮪 | atlantic bluefin tuna, bluefin tunny, northern bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus family: Scombridae |

taiseiyoumaguro タイセイヨウマグロ 大西洋鮪 | blackfin tuna Thunnus atlanticus family: Scombridae |

References & Further Reading

- [Adolf, 2019]: Steven Adolf. Tuna Wars: Powers Around the Fish We Love to Conserve. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham. 2019.

- [Akindo, 2021]: 知ってみよう すしのまぐろ | スシゴト | 回転寿司 スシロー (engl. Let's get to know - Sushi no Maguro - Sushiro, conveyor belt sushi restaurant). Akindo Sushiro Co. Ltd.. 2021. https://www.akindo-sushiro.co.jp/sushigoto/maguro/. Retrieved online on January 01, 2022.

- [Bergin & Haward, 1996]: Anthony Bergin, Marcus G. Haward. Japan's Tuna Fishing Industry: A Setting Sun Or New Dawn?. Nova Publishers, New York. 1996.

- [CCSBT, 2012]: Southern Bluefin Tuna Trade Data: Exploratory Analyses, CCSBT-CC/1209/1209/BGD 03. Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT), Canberra. 2012. Retrieved online on December 26, 2020.

- [CITES, 2010]: Governments not ready for trade ban on bluefin tuna. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), Geneva. 2010. https://www.cites.org/eng/news/pr/2010/20100318_tuna.shtml. Retrieved online on December 26, 2020.

- [Caton, 1994]: Caton A.E. (editor). Interactions of Pacific tuna fisheries Volume 2 Papers on biology and fisheries, Review of aspects of southern bluefin tuna biology, population and fisheries. In World meeting on stock assessments of bluefin tunas: strengths and weaknesses. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. 1994.

- [Chiezo, 1992]: 知恵蔵 : 朝日現代用語. Chiezō : Asahi gendai yōgo.. 朝日新聞社. 1992.

- [Cruz-Castán et al., 2019]: Roberto Cruz-Castán, Sámar Saber, David Macías, María José Gómez Vives, Gabriela Galindo-Cortes, Sergio Curiel-Ramirez, César Meiners-Mandujano. A possible new spawning area for Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus): the first histologic evidence of reproductive activity in the southern Gulf of Mexico. Aquatic Biology. Iranian Society of Ichthyology, Fisheries Department of the University of Tehran, PeerJ (O'Reilly and SAGE). 2019.

- [Ellis, 2008]: Richard Ellis. Tuna: A Love Story. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, New York. 2008.

- [Evans et al., 2012]: Karen Evans, Toby A. Patterson, Howard Reid, Shelton J. Harley. Reproductive Schedules in Southern Bluefin Tuna: Are Current Assumptions Appropriate?. PLOS One. Source.Volume 7 (4). Public Library of Science, San Francisco. 2012.

- [FAO, 2020]: The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA), Sustainability in action 2020. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. 2020.

- [Farley & Ohshimo, 2019]: J. H. Farley, S. Ohshimo. Review and insights into the differences in reproductive parameter estimates between Eastern and Western Atlantic bluefin tunas stocks. ICCAT. Source.Volume 75 (6). International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas, Madrid. 2019.

- [Globefish, 2016]: An overview of the global tuna market. GLOBEFISH Highlights. Issue 4. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. 2016.

- [Hibino, 1999]: 光敏 日比野. すしの歴史を訪ねる (engl. Visit the History of Sushi). Iwanami Shoten (岩波書店), Tokyo (東京都). 1999.

- [Ikuta, 2010]: 生田與克. たまらねぇ場所築地魚河岸 (engl. I can't wait to go to Tsukiji Fish Market!). 学研教育出版 : 発売元学研マーケティング (Tōkyō : Gakken Kyōiku Shuppan : Hatsubaimoto Gakken Māketingu). 2010.

- [MIC, 2020]: 消費者物価指数、年平均 1970~2019 (engl. Consumer Price Index (CPI), Annual average 1970-2019). Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (総務省 統計局). 2020. Retrieved online on December 26, 2020.

- [Nagano & Kibi, 2021]: Yusuke Nagano, Ayaka Kibi. Bluefin tuna sells for low pandemic price at Toyosu’s 1st 2021 auction. asahi.com, The Asahi Shimbun Company, Tokyo. 2021. http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14083726. Retrieved online on January 06, 2021.

- [Nakahara, 2019]: 中原 一歩. 「㐂寿司」のマグロは美しい。「㐂寿司」の365日。 (engl. Tuna Sushi is beautiful. 365 days of Sushi.). dancyu.jp, President Inc.. 2019. https://dancyu.jp/read/2019_00001129.html. Retrieved online on January 01, 2022.

- [Nikkei, 2009]: マグロ、48時間熟成でうまみ増加 くら寿司と東大院 (engl. 48-Hour Aging of Tuna Increases Umami in Tuna, Kura Sushi and the University of Tokyo). Nikkei Inc., Tokyo (日本経済新聞社、東京都). 2009. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXMZO51891530X01C19A1LKA000/. Retrieved online on December 26, 2020.

- [Noguchi, 1990]: 吉野 昇雄. 鮓・鮨・すし―すしの事典 (engl. Encyclopedia of Sushi). Asahiya Publishing (旭屋出版), Tokyo (東京都). 1990.

- [Sawada, 2013]: Yoshifumi Sawada, Toshio Kaga, Yasuo Agawa, Tomoki Honr Yo, Yang-su Kim, Masahiro Nakatani, Tokihiko Okada, Amado Cano, Daniel Margulies, Vernon Scholey. Growth Analysis in Artificially Hatched Pacific Bluefin Tuna. Aquaculture Science. Source.Volume 61 (3). Japanese Society for Aquaculture Science. 2013.

- [Shimose et al., 2009]: Tamaki Shimose, Toshiyuki Tanabe, Kuo-Shu Chen, Chien-Chung Hsu. Age determination and growth of Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, off Japan and Taiwan. Fisheries Research. Source.Volume 100 (2). Elsevier, Amsterdam. 2009.

- [Shimose, 2015]: Tamaki Shimose, Taiki Ishihara. A manual for age determination of Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis. Bulletin of Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency. Source.Volume 40. Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency, Kanagawa. 2015.

- [Tokyojin, 2007]: 東京人、第22巻 第1号. 東京都文化振興会. 2007.

- [Tsuchida et al, 2020]: 美登世 土田、潤 髙橋、秀美 佐藤. すしのサイエンス:おいしさを作り出す理論と技術が見える (engl. The Science of Sushi: Seeing the Theory and Technology Behind the Deliciousness of Sushi). Sibundo Shinkosha (誠文堂新光社), Tokyo (東京). 2020.

- [Williams, 1989]: S.C. Williams. The Japanese Tuna Markets: A Fundamentalists'v View. SPC/Fisheries 21/Information Paper 15. South Pacific Commission, Noumea. 1989.

Image Credits

City Foodsters. Maguro marinated in sake. flickr.com. License: Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0). Changes made: sharpening, cropping.

D. Schilder. Zuke Maguro Sushi. License: copyrighted ©.

D. Schilder. Toro Maguro Sushi. License: copyrighted ©.